The science behind rhyme, rhythm and repetition. / Getty ImagesWhy is it that many people can’t remember where they put their car keys most mornings, but can sing along to every lyric of a song they haven’t heard in years when it comes on the radio? Do song lyrics live in some sort of privileged place in our memories?

The science behind rhyme, rhythm and repetition. / Getty ImagesWhy is it that many people can’t remember where they put their car keys most mornings, but can sing along to every lyric of a song they haven’t heard in years when it comes on the radio? Do song lyrics live in some sort of privileged place in our memories?

The science of why you can remember song lyrics from years ago

by The Conversation

Music has a long history of being used as a mnemonic device, that is, to aid the memory of words and information. Before the advent of written language, music was used to orally transmit stories and information. We see many such examples even today, in how we teach children the alphabet, numbers, or – in my own case – the names of the 50 states of the US. Indeed, I’d challenge even any adult reader to try and recall the letters of the alphabet without hearing the familiar tune or its rhythm in your mind.

There are several reasons why music and words seem to become intricately linked in memory. Firstly, the features of music often serve as a predictable “scaffold” for helping us to remember associated lyrics.

For instance, the rhythm and beat of the music give clues as to how long the next word in a sequence will be. This helps to limit the possible word choices to be recalled, for instance, by signalling that a three-syllable word fits with a particular rhythm within the song.

A song’s melody can also help to segment a text into meaningful chunks. This allows us to essentially remember longer segments of information than if we had to memorise every single word individually. Songs also often make use of literary devices like rhyme and alliteration, which further facilitate memorisation.

Sing it

When we have sung or heard a song many times before, this song may become accessible via our implicit (non-conscious) memory. Singing the lyrics to a very well-known song is a form of procedural memory. That is, it is a highly automatised process like riding a bike: it’s something we are able to do without thinking much about it.

One of the reasons music is so deeply ingrained in memory in this way is because we tend to hear the same songs many, many times throughout our lifetimes (more so, than say, reading a favourite book or watching a favourite film).

‘I just can’t get you out of my head’: we tend to remember songs and lyrics quite easily. /Getty Images

‘I just can’t get you out of my head’: we tend to remember songs and lyrics quite easily. /Getty ImagesMusic is also fundamentally emotional. Indeed, research has shown that one of the main reasons people engage with music is because of the diversity of emotions it conveys and evokes.

A wide range of research has found that emotional stimuli are remembered better than non-emotional ones. The task of trying to remember the ABCs or the colours of the rainbow? is inherently more motivating when set to a catchy tune – and we can remember this material better later on when we make an emotional connection.

Music and lyrics

It should be noted that not all previous research has found that music facilitates memory for associated lyrics. For instance, upon the first encounter with a new song, memorising both the melody and associated lyrics is harder than memorising just the lyrics. This makes sense, given the multiple tasks involved.

However, after getting over this initial hurdle and being exposed to a song several times, more beneficial effects seem to kick in. Once a melody is familiar, the associated lyrics are generally easier to remember than if you tried to memorise these lyrics without a tune behind them.

Research in this area is also being applied to assist people with various neurodegenerative disorders. For instance, music seems to help those with Alzheimer’s disease and multiple sclerosis to remember verbal information.

So, the next time you put your car keys in a new spot, try creating a catchy song to remind you of their location the next day – and, in theory, you shouldn’t forget where you’ve put them so easily. Reference

Reference

Written by Kelly Jakubowski

Provided by The Conversation

- ※ Picks respects the rights of all copyright holders. If you do wish to make material edits, you will need to run them by the copyright holder for approval.

more from

The Conversation

-

The Conversation

To spur the construction of affordable, resilient homes, the future is concrete

2025-06-26 00:00:00

2025-06-26 00:00:00 -

The Conversation

How the end of carbon capture could spark a new industrial revolution

2025-06-25 00:00:00

2025-06-25 00:00:00 -

The Conversation

After the smoke clears, a wildfire’s legacy can haunt rivers for years, putting drinking water at risk

2025-06-25 00:00:00

2025-06-25 00:00:00 -

The Conversation

How pterosaurs learned to fly: scientists have been looking in the wrong place to solve this mystery

2025-06-24 00:00:00

2025-06-24 00:00:00

BEST STORIES

-

ETX

'More microplastics in glass bottles than plastic: study'

2025-06-23 00:00:00

2025-06-23 00:00:00 -

Visit Dubai

Dreaming of a Dubai beach holiday?

2025-06-21 00:00:00

2025-06-21 00:00:00 -

AllblancTV

Super Morning Fullbody Home Workout (Part 1/2)

2025-06-23 00:00:00

2025-06-23 00:00:00 -

Inven Global

Netmarble Launches Game of Thrones: Kingsroad on iOS, Android and PC

2025-06-21 00:00:00

2025-06-21 00:00:00

Lifestyle

-

The Conversation

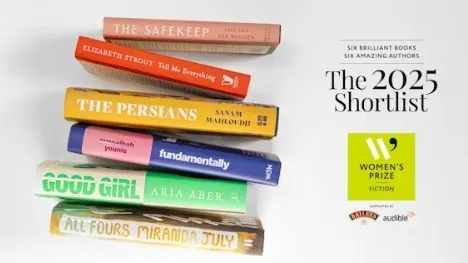

Women's prize for fiction 2025: six experts review the shortlisted novels

2025-06-17 00:00:00

2025-06-17 00:00:00 -

The Conversation

'Godfather of AI' now fears it’s unsafe. He has a plan to rein it in

2025-06-16 00:00:00

2025-06-16 00:00:00 -

The Conversation

If people stopped having babies, how long would it be before humans were all gone?

2025-06-10 00:00:00

2025-06-10 00:00:00 -

The Conversation

Debunking 5 myths about when your devices get wet

2025-06-03 00:00:00

2025-06-03 00:00:00